Michelle Skowbo

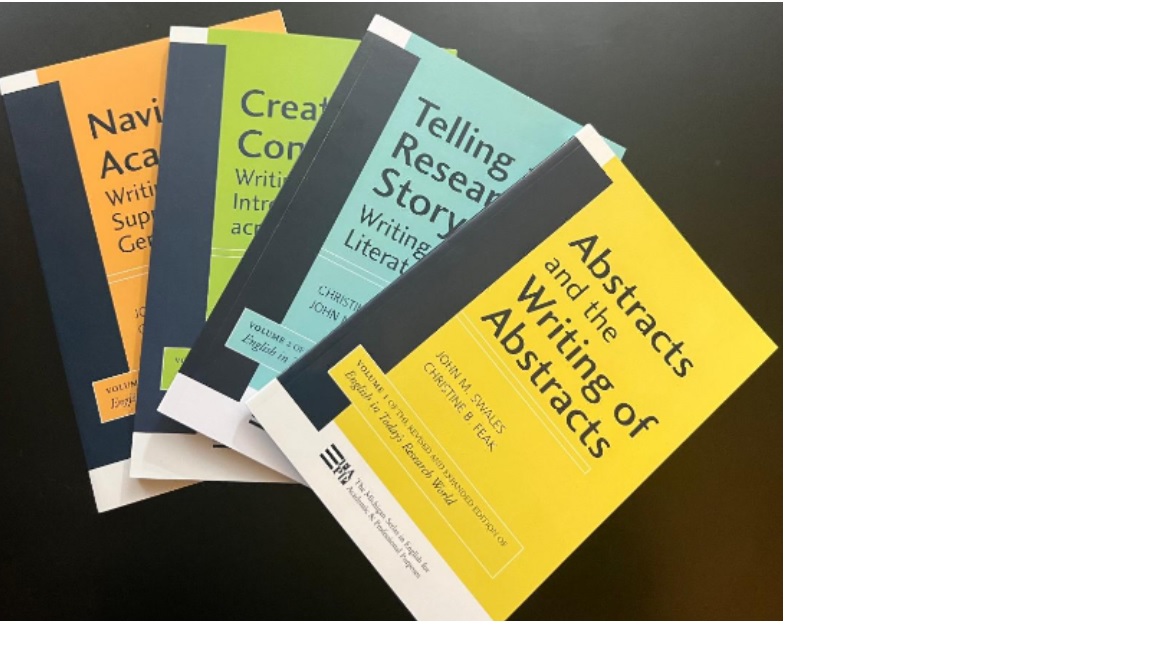

The Michigan Series in English for Academic & Professional Purposes, Volume 1, 2, 3 4

By John M. Swales and Christine B. Feak

By Sonia Estima and Kara Mac Donald

Academic Writing for Graduate Students (Swales & Feak, 2004), with subsequent editions, is a ubiquitous text used in/for academic research writing courses. The smaller short texts with a specific focus on particular aspects of writing a research manuscript were published a few years after (i.e. 2009). They also have been fundamental go-to-texts for academic research writing instruction. This review describes the value of the English for Academic & Professional Purposes series text as publishing educators, we have strengths and weaknesses across the different components of a research publication and a quick go-to concise source is beneficial. Also, for educators who are teachers of academic and research writing, there may not be a need based on student population to review all aspects of an academic research publication, and this series can offer an accessible engagement on particular areas of a research manuscript.

The series consists of four volumes: Volume 1: Abstracts and the Writing of Abstracts; Volume 2: Telling a Research Story: Writing a Literature Review; Volume 3: Creating Contexts: Writing Introductions across Genres; and Volume 4: Navigating Academia: Writing Supporting Genres. The structure and content of each booklet are summarized below.

Volume 1: Abstracts and the Writing of Abstracts

The text addresses four types of abstracts: research article abstracts, abstracts for short communication, conference abstracts and PhD dissertation abstracts. The format for a research article abstract is composed of five moves (steps). Move 1 and 2, Getting Started, sets up the approach for the focus of the abstract and draws a connection between the first and second sentence. There are four main approaches to beginning an abstract: i) starting with a real-world practice, ii) Starting the objective of the study, iii) Starting with researcher’s actions, iv) Starting with an existing issue or problem. Move 3, Compressing Methods Descriptions, is where the recap of the research processes is shared. Move 4, Moving On: Results, presents the findings. Move 5, Concluding a Traditional Abstract, is one where a positive view and/or outcome of the research is highlighted. Closing the section of the booklet is an examination of whether there is a need to problematize as part of the background statement related to the research focus, with a conclusion that although it is common, it is not required.

Abstracts for short communication accompany short pieces in journals (e.g... short communications, technical notes, research notes, scientific letters, and case studies) and may also be as long as abstracts for research articles and typically follow the same structure outlined above. However, in some cases, these abstracts can be much shorter and this is when there is a need to look at how they are structured. They often consist of two sentences, where the first sentence consists of Move 3 and 4 (i.e., methods and results), and the second sentence consists of Move 5 (i.e., implications).

Conference abstracts consist of six moves: Move 1: Describing and issue in the field, Move 2: Stating how the current research fills the need, Move 3: Methods, Move 4: Findings, Move 5: Significance of results, Move 6: Implications and/or limitations. The additional move is there to assist to draw in the review committee in conference proposal review. The second part of this section of the booklet addresses the rating process that conference abstracts undergo, the role of the sole authors, conference titles and related topics.

PhD dissertation abstracts are addressed separately as they are unique in that they may be evaluated separately from the thesis itself and that the abstracts often have a standard format of being a maximum of 350 words. The challenge for authors is that there is a lot of information to be shared, from the background information on the issue, problematizing the issue,to describing the methods, findings, and implications. Authors may wish to include many details and make broad claims, while thesis advisors may wish to have more concise content and more limited claims.

In each section of the booklet, the authors provide tasks for the readers that are related to the specific types of abstracts at that point in the discussion. These tasks are accompanied by sample abstracts or portions of abstracts from different fields as models and/or for the reader to analyze to have closer examination of the different structure and language of each type of abstract.

Volume 2: Telling a Research Story, Writing a Literature Review

The text addresses the rationale for reviewing the literature, types and characteristics of literature reviews and related topics. Then, it guides the reader on getting started with the literature review: the drafting and revising processes, and the development of creating an original discussion of previous published work and criteria for assessing the final product.

There are three rationales for doing a review literature: i) to ensure that the research study has not already been conducted, duplicating findings that already exist (replicating studies with a specific purpose is suitable), ii) to understand and demonstrate how your study fits in the work of the larger field, iii) to identify you and your works as part of the professional field.

Four principal types of literature reviews are described. First, are narrative literature reviews, where relevant research is summarized to frame the research study, as these are often in theses, research articles, research, and grant proposals. Second are systematic literature reviews, most frequently found in health sciences, the criteria for selecting some work for review and others not, is clearly stated to better understand the status of the research at hand and the implications. Third, Meta-Analysis reviews multiple studies with the same research question to capture an understanding of the status of a specific area that cannot be obtained through one individual study. Fourth, focused literature reviews examine one specific aspect (e.g. methodology, approaches of data analysis) of previous research studies addressing a particular topic, with the goal of analyzing the implications of selecting one method over another for data collection, analysis and interpretation. The structure of a literature review and frequent advisor recommendations are shared.

Next, the task of starting the literature process is addressed, as it can be daunting for an unexperienced researcher. Although Reader Tasks (exercises for readers to do addressing the concept at hand as they read to personalize the content) are common throughout this volume and all volumes in the series. The reader tasks in this section are particularly useful to understand the structure of the literature review, organizing the published description of the literature, and making connections between each section of the literature review to form a cohesive discussion (i.e. not simply have paragraphs of independent summaries of different research and/or topic areas. The following section offers a case study of a PhD student to unpack the process of drafting a literature review, revising, and redrafting it, with a description of how to step back and objectively assess the final review drafted.

The text closes by stating that it has taken a macro-structural approach to outlining and describing the literature review. However, it closes with the reminder of the importance that a researcher is crafting his/her own unique narrative of the field’s work to frame and support his/her study. And as always, the volume is filled with activities for the reader to go through at each stage of the discussion in drafting literature reviews.

Volume 3: Creating Contexts, Writing Introductions across Genres

Volume 3 of the series addresses writing introductions across a variety of academic genres in different disciplines. The book can be a valuable resource for an individual student or scholar seeking information or advice on a particular form of introduction, or it may be used as part of the curriculum for an academic writing course for graduate students. This revised edition contains some changes from the previous publication, focusing less on the distinction between native and non-native speakers, and more on the distinction between junior academics starting out their careers, and more senior scholars established in their practice. The authors use a large corpus of material from a wide range of fields and genres for their analysis and review.

As with the two previous volumes, each topic is followed by a series of tasks that include different types of exercises as well as samples of work followed by reflection questions, designed to generate discussion and consideration. These tasks are accompanied by a separate set of online commentary by the authors to support the main text: www.press.umich.edu/esl/compsite/ETRW/. The online commentary offers answers to some of the exercises, as well as provides additional points of view and diverging opinions to the questions raised in the text.

The book is divided into several sections, starting with a general discussion and preliminary considerations, including the questioning of when the introduction should be written, before or after the work is completed, and the overall structure of the introduction. Rather than taking a prescriptive approach to the topic, the authors provide different views and perspectives, allowing readers to come to their own conclusion. The subsequent sections provide a range of genres that graduate students and academics would likely encounter, such as writing introductions to course papers, book reviews, critiques and reviews of journal articles and book chapters, reports, proposals, and doctoral dissertations.

The largest portion of the book, however, is devoted to discussing writing introductions to journal articles, which both contain a vast amount of research devoted to the topic and occupy a central position in academic writing. In this section, the CaRS Model (creating a research space) is used as a framework for discussion. The model is not intended as a template to be followed step by step, but rather as a tool to guide the discussion and help the reader.

Another feature of the book that novice writers may find very useful is the inclusion of several “Language Focus” sections in all volumes. Creating Contexts offers important points on linguistic form that can guide graduate students starting out with this type of writing. Some of the topics addressed in this volume include managing the flow of ideas from old to new information, how to express agreement and disagreement, and the use of the ‘attitudinal’ or polite past in English.

The volume ends with a discussion of writing introductions to dissertations, which can vary greatly across disciplines. Rather than trying to cover the entire realm of possibilities, the authors try to focus on some common characteristics of dissertation introductions, starting with the purpose of the study, the research question, and the hypothesis. They end with a list of reflection questions to engage the reader.

As with the previous volumes, this one is not necessarily intended to be followed in order from beginning to end, but rather to help position the reader as a writer within the specific genre and the context in which it is written.

Volume 4: Navigating Academia, Writing Supporting Genres

The final volume of the series focuses on the less visible supporting genres that accompany academic writing and research. Navigating Academia addresses a variety of writing genres that permeate university and academic work and may be challenging for those new to the field. The types of genres addressed here include statements of purpose for admission to graduate school, letters of recommendation, and even email responses to professors and advisors.

One reason students may have difficulty with this type of writing is that it may be less prominent, with much less research and few examples available to students or the novice scholar just starting out. Volume 4 differs a little from the previous, as it pays greater attention to the social aspect and the impact of the writing on its intended recipients, who will often be responsible for the outcomes of an application or the response to a request.

As with the previous titles, Navigating Academia does not need to be covered in the order it is presented. Each section or topic can be studied independently, depending on the specific needs of the readers and where in their career they may be, from entering graduate school, to navigating their academic practice. Volume 4 follows the same general organization as the previous books, with a series of tasks to accompany each topic and help guide the discussion and suggested practical exercises. It is also supported by an online commentary that can be found at: www.press.umich.edu/esl/compsite/ETRW/.

The first topic addressed in Navigating Academia is of critical importance to those thinking about or planning to apply for graduate school. It discusses the difference between statements of purpose and personal statements, which is often a requirement for most graduate program admission. It then moves to cover a series of different types of academic correspondence a student is likely to encounter, such as communicating with advisors and committee members, communicating with co-authors, and sending email requests and reminders.

For those who may be a little further along in their academic career, the book addresses the need to establish oneself professionally and the types of writing that may be encountered, such as grant applications, placing announcements for assistant positions, fellowship applications, and writing letters of recommendation.

As in the previous volumes, it provides a series of “Language Focus” sessions to address common linguistic challenges associated with the genres presented: the use and significance of positive and less positive language in letters of recommendation, how to politely stand your ground, and expressing gratitude, among others.

The book includes sections intended to support the publication process: writing manuscript submissions, responding to reviewers and editors, and writing acknowledgements. And it ends with an overview of writing an academic curricula vitae, submitting external job applications, and writing a statement of teaching philosophy.

It should be noted that none of the volumes within the series cover all the specifics of the different disciplines, as it would be impossible to do so. Nonetheless, the authors manage to provide guidance and insight to allow the reader to reflect and understand the particulars of each genre and what they need to do and where to go for additional support. The examples in this volume provided and the discussions center around the American university system, and the authors point out areas where differences may exist in the practice of other countries, being of particular interest to foreign students preparing to do their graduate work in the US. The series provides an awareness of disciplinary differences and examples from a variety of fields, from engineering to the medical field to the humanities, providing relevant guidance to students of a wide range of academic disciplines.

Conclusion

The Swales and Feak (2004), Academic Writing for Graduate Students (and other editions, 1st and 3rd) is a fundamental text for graduate writing students across various fields, outlining each section across chapter serving a comprehensive text. The specific value of The Michigan Series in English for Academic & Professional Purposes, Volume 1, 2, 3 4, by the same authors, is that each volume allows the researcher/research writing instructor to focus in on one aspect of the research article as appropriate. Having slender, highly accessible mini volumes, paralleling the content in the main research writing text, making writing research articles all that more accessible to novice researchers and writers.

Reference

Swales, J. M., & Feak, C. B. (2004). Academic writing for graduate students: Essential tasks and skills (2nd ed.). Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press.